A World of Color

The science behind the dazzling displays of marine fish

By Joe Curtis, Photographs by Kara Wall

One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish, right? If only it were so simple.

Fish use color as a multi-purpose tool to interact with their surroundings, displaying drastically different palettes across their life stages. They can even change color based on minute-to-minute needs. Since that little yellow fish today could grow into a big blue fish tomorrow, we can't rely on color alone to identify a fish species.

So why do fish change color? Here are four of the most common roles color can play in the world of marine fish:

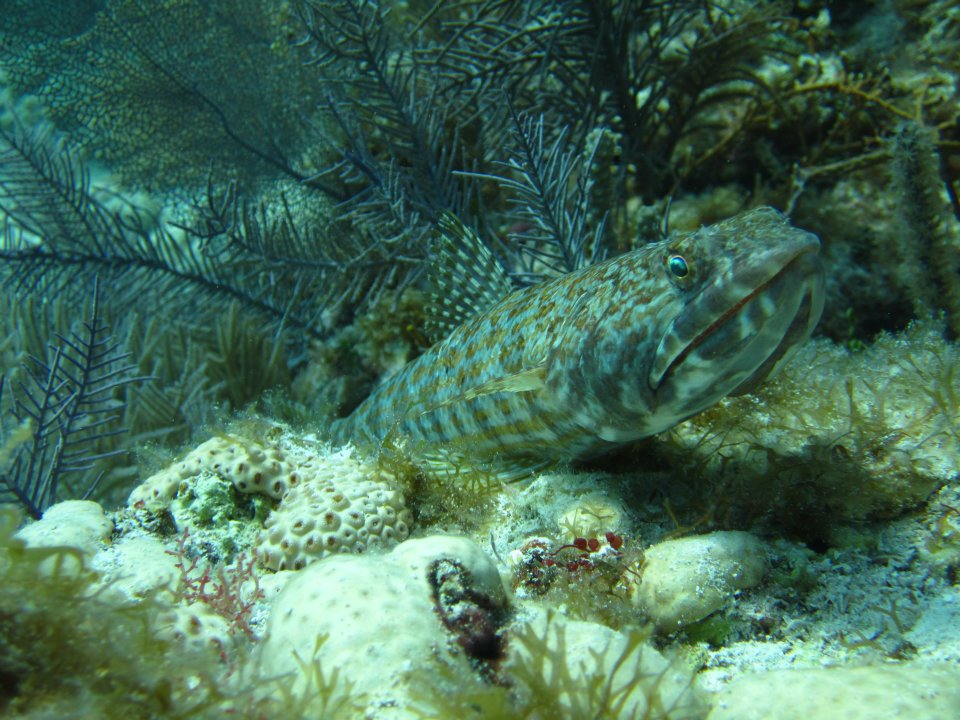

1. You can’t see me

Scuba divers can see flamboyantly colored clownfish and butterflyfish from great distances, but hungry predator's (like a barracuda) can't. These fish employ a strategy called disruptive coloration; they use stripes, bars, and dots of different hues to break up their outline and obscure their recognizable fishy shape.

Instead of seeing a tasty morsel, predators may instead perceive random and nonsensical blotches of movement, allowing prey to hide in plain sight. Many fish are also colorblind to the vibrant hues of coral reefs, so a predator might see a fluorescent orange clownfish as a much more cryptic series of grey and white stripes.

Other species such as the scorpionfish and flatfish mimic the color of rock and sand, blending seamlessly into the background of their marine environment. Some fish can even change their pigmentation as they move between habitats, shifting color over time to more-effectively evade potential predators.

2. Warning!

Touching anything colorful is risky: you might receive a painful sting, bite, or puncture. The same vibrant blues, stunning reds, and neon yellows that make fish popular aquarium pets also serve as a gigantic “hands off” sign to other marine animals.

Bright warning coloration, also extremely common on land (think poison dart frogs and monarch butterflies), is a convenient way for venomous fish to tell their neighbors that they’re packing heat.

Lionfish for example, a venomous invasive species which has ravaged the reefs of South Florida, are generally avoided by native predators, likely due in part to their bright warning colors.

As with any popular trend, fish with warning coloration often inspire copycats, nonvenomous fish that have evolved over millennia to don the same flashy shades. The copycats don't produce energetically-expensive toxins or venoms, but since they look poisonous, predators still avoid them.

3. Hey there good lookin’

Sex appeal is not lost on fish. Many males, especially in parrotfish and wrasse species, will ditch the drab color schemes of their youth for flashy adult displays. Their bright colors attract fertile females by indicating that the males are available and willing to mate.

Some fish will rapidly flash an array of colors and dart back and forth in elaborate maneuvers, repeatedly demonstrating to females their machismo and prowess. Sub-par males can actually take advantage of color-segregated life stages, donning the outer appearance of a female and sneakily depositing sperm in mating aggregations while the dominant male is occupied.

Sexually divided color schemes can also be very confusing when you're trying to identify a species. Males and females can look very different from each other, displaying a wide range of coloration throughout their lives. With so many color morphs, even a single species can take up pages of a field guide.

4. Head towards the light

One of the most memorable scenes in Finding Nemo involves a mad dash toward (and subsequently away from) a floating blob of light: a lure dangling in front of a toothy, terrifying anglerfish’s mouth. Most deep sea fish use bioluminescence (literally, “life light”) to attract other creatures in the pitch black abyss.

Sometimes known as phosphorescence, displays of bioluminescence on a moonless night are like a Disneyland fireworks show. Brilliant hues of green, red, yellow, and blue sparkle and dazzle throughout the water column. Among myriad bioluminescent organisms, the most common fish on earth (bristlemouth) as well as the smallest shark (pygmy shark) both glow when disturbed, in this case to startle would-be predators.

Colors of course serve more than four purposes in the life of a marine fish, but these are by far the most common. We should be grateful: the pathways of evolution and adaptation that have painted fish in such colorful pandemonium keep things interesting for us land-dwellers too. Just imagine how boring life would be if there was only one fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish.

Joseph Curtis is pursuing a Master’s degree from the University of South Florida in the Fish Ecology Lab, focusing on the effects of invasive lionfish. He is an avid SCUBA diver and has traveled around the world exploring marine habitats. He can be reached at Jcurtis@mail.usf.edu.

Kara is pursuing a Master's degree studying marine ecology at the University of South Florida. Her research on marine ecosystems affords her unique opportunities to photograph ocean life. See her photos on kwoceanphoto.com and reach her at Krwall@usf.edu.