An ode to the elegance of sediment

On a stroll down an icy beach, Holly McKelvey meditates on stories written in rock.

By Holly McKelvey

On a nose-bitingly icy December morning, I walked along a snow-covered beach in my small university town of St Andrews, Scotland. Leaning down, scarf wrapped close against my face, I brushed away some snow from the ground with a gloved hand.

Underneath the snow, there was sand. Predictably. I dug deeper. Underneath that, I found a surprise... another layer of snow?

The answer was this: the night before, snow had cloaked our small beach-side town in white. During the night, the tide had come in, and in the bitter nighttime cold, it did not melt the snow. Instead, the waves deposited a second layer of sand, and went out again. The next morning more snow fell onto this fresh sand, blanketing the beach anew.

Snow, sand, snow, sand. An unusual occurrence, one which melted away in the daytime with the next tide. But before washing out to sea, it elegantly illustrated of one of the most common processes on Earth's surface: sedimentation.

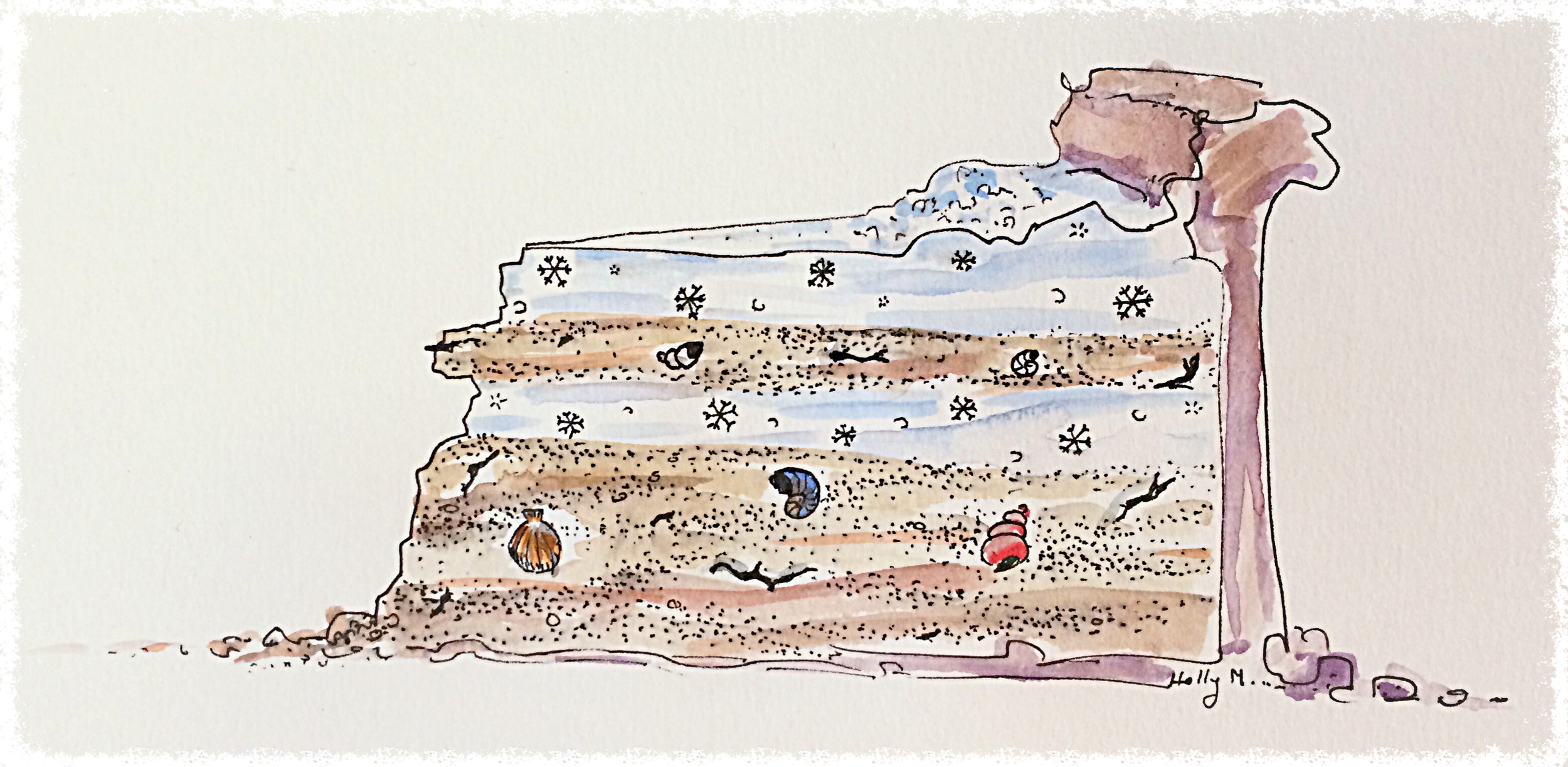

Sedimentation is the process by which particles of rock, sand, mud, plant matter and animal matter are deposited layer-by-layer, forming rock over time. The particles come from mountaintops, hillsides, fields, and river banks; they are moved ever downwards by the erosive forces of wind and rain.

Each particle carries clues to its history. And whole sediments, mosaics made up of particles, offer windows into the ancient environments that shaped them. Iron red sandstones are the legacy of ancient beaches; coal marks fallen leaves, the echo of a long-ago forest; chalky limestones cliffs speak of warm shallow seas suffused with corals and mollusks. Earth's ledgers are writ in stone.

Appreciating this, it is hard not to feel a sense of wonder at the processes that have created the rocks under our feet. As natural philosopher John Playfair wrote over two hundred years ago, standing before an ancient outcrop that told a particularly striking story: "we felt necessarily carried back to a time when the schistus on which we stood was yet at the bottom of the sea, and when the sandstone before us was only beginning to be deposited, in the shape of sand or mud, from the waters of the supercontinent ocean."

Looking into these outcrops is a lens into the Earth's deep past. In this distant past, we can see that the world was a fantastically different place, perhaps uninhabitable by species we would recognize today. And yet these same sedimentary processes that we observe today occurred then as well, linking that past inexorably to our present.

Peering back into time through layers of rock to map their meandering passage through the ages may be intriguing. But recognizing that something as ubiquitous and mundane as the ground we walk on tells a story, an elegant narrative shared by the whole of our planet? Intoxicating.

Early natural philosophers felt that sense of intoxication over two hundred years ago as they began to describe the geological unknown. We feel it today with the thrill of learning, discovering something new, or solving some fresh puzzle set before us. The scientist in us is, as ever, fighting to find answers.

As I stood there on that frozen beach, fingers sifting through an unexpected sequence of snow and sand, I felt awe. Simple sedimentation. What a wonder to understand the story of our past that it paints.

Holly McKelvey is a graduate student in Applied Ecology at the University of Poitiers, France, working on bio-indicators in stream ecology. She can be reached at holly.mc.kelvey@etu.univ-poitiers.fr