The Great Barrier Reef

Byline

By Paula Barbeito Morandeira

When I was a child, I used to go down to the corner shop, a kiosk where I spent most of my weekly allowance. Stickers, candy, marbles… my whole universe was there. One day, as I was glancing through the magazines, I suddenly came across one that grabbed my attention completely. As I turned the pages, I was entranced by the pictures. I wanted to look at every photograph in that magazine, but I needed to do it undetected: No money, no magazine. And suddenly, I found myself at the centerfold photograph of the magazine. I glanced at the seller: she was distracted, talking with another customer. This was my opportunity. Slowly, reverently, I spread out the photo and, little by little, I realized that I was in the ocean. I did not know what it was that I was looking at, but I could not take my eyes away from that picture. In fact, this picture would stay with me from then on. From intense blue to bottle green with transitions in turquoise crystalline. The seller looked at me. It was not necessary for her to say anything. No money, no magazine. I left the kiosk and the magazine behind, and returned home with one thing on my mind: “Australian Great Barrier Reef, by Yann-Arthus Bertrand”.

I pleaded with my mum for the next two weeks of allowance. I needed to buy that magazine and read everything about that colorful image. It worked. The next day I bought the magazine and spent the whole day lost in that article.

In 1770, the English explorer Captain James Cook left England with the mission of observing and documenting an eclipse of Venus. But his ship, The Endeavor, ran aground off the coast of Australia on a mysterious hard structure. While the crew repaired the boat, Cook, the naturalist Joseph Banks, and their daring scientific minds explored the structure they had hit. They would never know it, but they were the first to observe the largest and only living structure distinguishable from space, a total of 2,500 kilometers in length (that's longer than Italy). If it had been me, I do not know what would have been more impressive to me: the length, or the amazing biodiversity. More than 400 species of corals, with approximately 2,900 individual reefs; more than 1,500 fish species, seabirds, seahorses, whales, dugongs, and six out of the seven turtle species that inhabit our planet. All of that richness embedded in a sort of painter's palette. The Great Barrier Reef – which I'll refer to as the GBR from here on – has been evolving over the last 15,000 years. In 1981, the UNESCO declared the GBR a World Heritage Site.

Of course, this rich sanctuary also makes a major contribution to the Australian economy. Reef-related tourism alone creates 4,800 jobs. Approximately 500 commercial boats operate, bringing tourists out to dive and snorkel on the reef. Diving, together with commercial and recreational fishing, contributes around $6 billion dollars to the economy. These industries are the mainstay for the regional communities along the central and north Queensland coast.

Almost three centuries have passed since Cook and his mate were there. Only 20 years have passed since that afternoon that I stood in the kiosk leafing through that magazine. Enough time for things to change. Not so long ago, I switched on my laptop and what I saw was like a slap in the face:

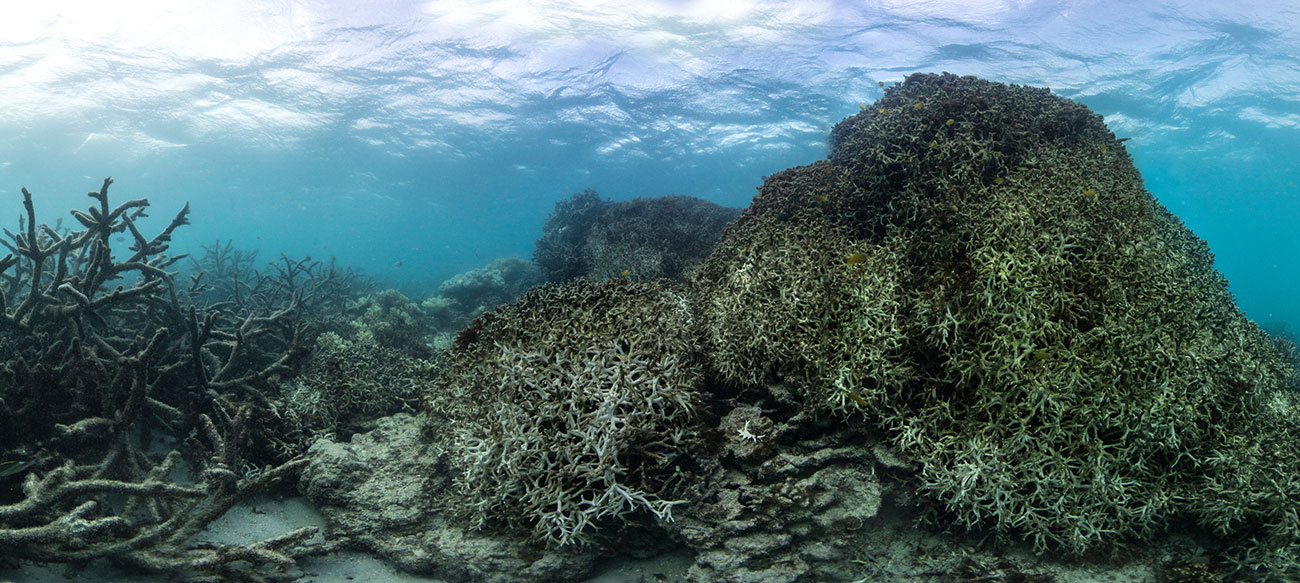

“35% of Australian GBR is dead”

“Survey confirms worst ever coral bleaching at GBR”

What has been happening, to cause the corals to bleach? Well, for one, our environment is being exposed to stresses too quickly for organisms to be able to adapt to them. As you probably know, CO<sub>2</sub> levels have been rising since the industrial age, an increase of nearly 40%. These high levels of CO<sub>2</sub> in the atmosphere are partially absorbed by the oceans, resulting in increased seawater acidity. Some marine organisms, including corals, respond poorly to acidity because it reduces their capacity to build their calcium carbonate-based skeletons.

The remaining CO<sub>2</sub> in the atmosphere has a second effect on our oceans: increased water temperatures. This has, in turn, an impact on coral communities. Corals – which, by the way, are animals, not plants – live in partnership with algae called zooxanthellae. Zooxanthellae provide food to the corals in exchange for shelter. 1 square centimeter of coral tissue alone contains around 1 million of these algae. But they dislike warm water. When oceans get atypically warm, corals eject the zooxanthellae; and their skeletons become white and sick. When the warming lasts too long, they can die.

This is not the first time that oceans have warmed. High temperatures have caused nine mass coral bleaching events in the GBR since 1979. Before this year, the worst events occurred in 1998 and 2002. But higher water temperatures due to climate change, in combination with this year's severe El Niño event, are pushing corals worldwide into danger; and the GBR is currently suffering the most severe bleaching episode yet recorded. Surveys have revealed that 93% of the individual reefs have been affected in some way, and almost a quarter of the coral over the entire GBR has been killed by this most recent bleaching event.

Recent studies show projections about what will happen to the GBR by mid-century. The prognosis is not optimistic. If the present CO<sub>2</sub> trajectory continues, the GBR may have shrunk to 10 per cent or less of its previous coverage. The economic implications would be disastrous – as well as the impacts on coastal protection. Reefs functions as important wave barriers; without them, many islands will be swamped.

As usual with environmental problems, there are a wide range of perceptions about the magnitude of the issue. From the scientific perspective, there are always optimistic researchers who have faith in coral's ability to adapt to higher temperatures, and who believe that the reef will be fine. On the other side of the aisle, many believe we are facing a point of no return: what is lost will never be recovered. But not everyone wants this point of view made public. The Australian Department of Environment itself intervened in the UN Report on Climate Change and World Heritage Sites to avoid mention of the GBR, on the grounds that it would hurt tourism. This occurred despite an open letter published by many small tourism operators, urging the government to recognize the severity of bleaching.

If we are not honest enough to recognize our responsibility in the global state of the environment, if we are not equipped to control the consequences of our actions, are we prepared for the uncertain shape of things to come?

Paula is a marine scientist and a graduate student in Sustainability, Society and the Environment at the University of Kiel, Germany. She loves the ocean and listening to the stories of the elderly. In her free time you'll find her going for long walks and hikes, scribbling on a small piece of paper, or listening to music. Photo courtesy of Yul Sánchez.