NIght Fishing The Cleveland shoreline

Can the act of fishing change the way Cleveland thinks about its most damaged watersheds?

By Matt Stansberry, Illustration by David Wilson

Standing on the break wall separating Cleveland from Lake Erie, my brother and I squint at the hordes of anglers descending on the jetties at nightfall. They are mostly men, risking life and limb to intercept migrating walleye, a toothy, nocturnal apex predator. These fish are the region’s premiere table fare, and catching them is serious business. My brother and I acknowledge the fishermen, and resume casting out into the inland sea.

Behind us looms the city, a glowing post-industrial metropolis built for an economy that no longer exists. Cleveland’s population has dwindled to 390,000 people from over a half million people in 1990. It can feel empty, like a machine abandoned, still clanging and thrumming on the lake.

For many North Americans, Cleveland will always be “The Mistake on the Lake,” the place where the Cuyahoga River caught fire in 1969 – a symbol of economic and environmental ruin. The waterfront in the city center is still dominated by heavy industry and sewage treatment. Rust and excrement – this is the legacy of early city planners using lake Erie as a garbage dump and toilet.

For two centuries, Cleveland has buried this lake, its greatest asset. But today, Lake Erie is being touted as a way to save the city, a way to keep the 20-somethings from moving away in droves, a natural antidote to the region’s crippling seasonal depression. And our walleye, fish full of teeth and spines, are a beautiful part of that.

From now till ice-up, millions of walleye are migrating and feeding, moving from the eastern corner of the lake to the shallow western basin. Clevelanders are flocking to the city breakwalls at night to catch them. The act of fishing is transforming the waterfront, subverting the history of treating the lake like dump.

After four decades of environmental regulation and economic collapse, the industrial toxins found in our fish are declining. The Ohio Division of Wildlife provides fish fillets, tested by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and the Ohio Department of Health every year. “Over the long haul, we have seen the slow decline in the amount of toxins showing up in fish flesh,” says Kevin Kayle, Fisheries Biology Supervisor at Fairport Harbor Fisheries Research Station, for the ODNR Division of Wildlife. “Probably our biggest concern is atmospheric mercury, most likely from emissions and coal burning power plants, but that’s a challenge across the region, not just for Lake Erie. PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) have been below actionable levels in Lake Erie’s primary food fish (perch and walleye) for a couple of decades.”

Today more fish are caught on Lake Erie for human consumption than on the other four Great Lakes combined. All fish in Ohio have small amounts of chemical contaminants. But by limiting meals, consumers can avoid building up contaminants to harmful levels. The Ohio EPA’s sportfish consumption health advisory recommends eating up to two meals per week of perch or sunfish, or one meal per week of most other species in Lake Erie. In fact you could eat just about any fish you wanted, once a week, every week of the year. The recommendations are conservative, geared toward protecting childbearing women, senior citizens and people with compromised health. A healthy person could eat Lake Erie walleye every day.

The days start to die early at the end of October. At dusk, the break wall at Cleveland’s Edgewater Park explodes with life—Ring-billed gulls, Bonaparte’s gulls, Herring Gulls. The birds wheel in from behind us, flying overhead and out over the water. Some dive for the baits we cast. A horned grebe looks us over with a mix of curiosity and contempt. A black-crowned night heron circles above the jetty, calling a hoarse and angry wok wok wok. Diving ducks fly by quickly—most likely red-breasted mergansers—hugging the water. Hundreds of thousands of these ducks stop over to refuel on Lake Erie’s abundant baitfish each winter; a staggering 80 percent of this species' North American population can be found floating just off the Cleveland shoreline. Large fish attack smaller prey, splashing on the surface nearby; the water birds take full advantage. Predators converge from above and below to eat the silvery shoals of small fish. It's an explosion of life.

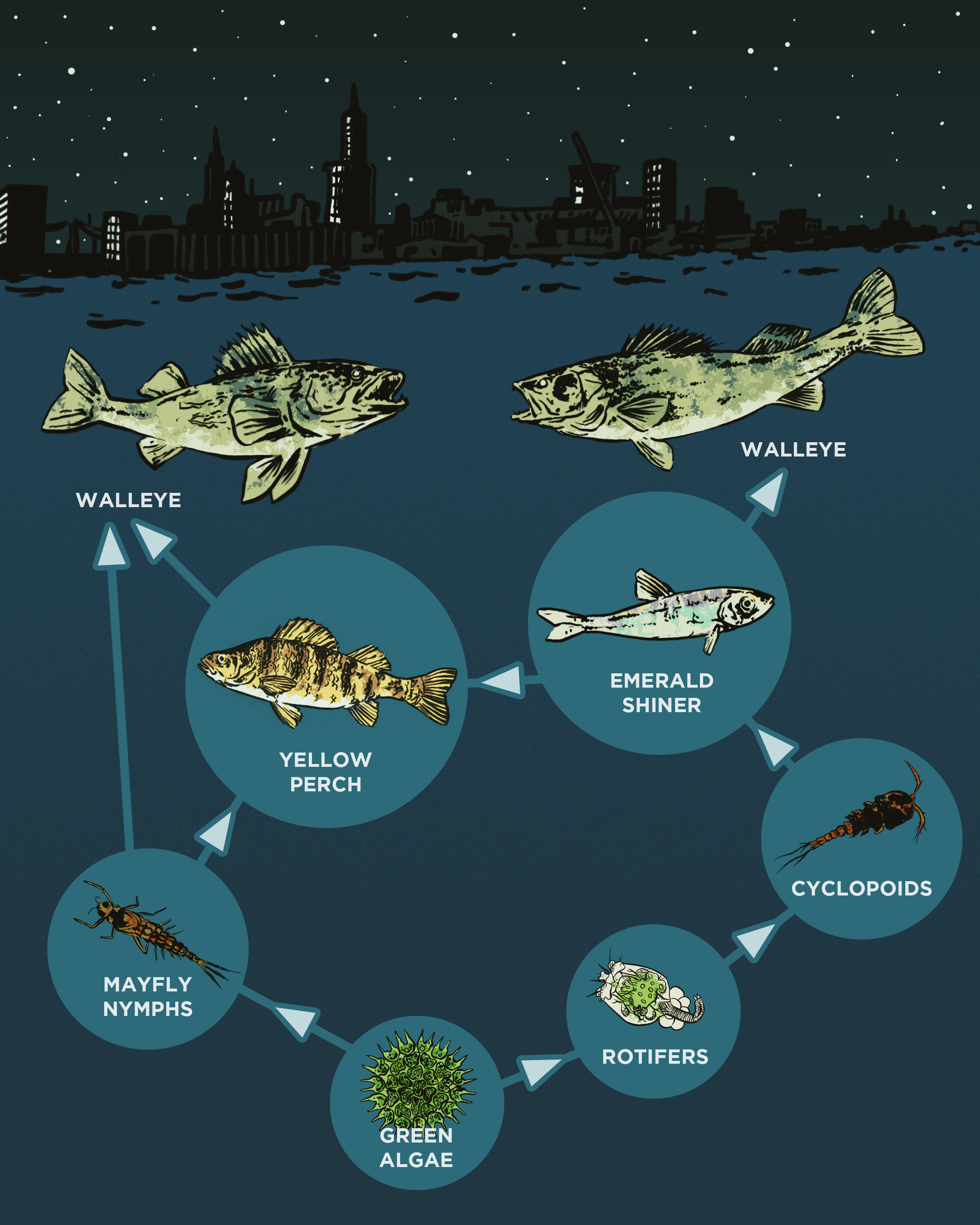

Standing above on the break wall, we are hunting the hunters. Walleye are usually considered a deep-water, offshore species. But at the end of the year, when forage fish like Emerald Shiners and Gizzard Shad move inshore, the walleye follow them, putting on weight that will help them to develop their eggs and overwinter. And the walleye don't just follow their prey through the lake; they literally follow bait wherever it goes, oftentimes right along the shoreline, and right to the top of the water column.

“In late fall, when the water temperature dips below 50 degrees, a sunny day can really heat up the top five to ten feet of water,” said Travis Hartman, Fisheries Biologist at ODNR’s Sandusky Fish Research Unit. “Shad seek that warmer temperature. As the day progresses, they move up into the warm water and the walleye follow them.”

By sundown, the water is at its warmest and the highest concentration of bait is on the surface. Walleye have a visual advantage in low light. “It’s well-published how great their night vision is,” Hartman said. “If you look at those big eyes and where they’re positioned, they are designed to attack from below.”

More than 23 million adult walleye, at least two years old, are swimming in Lake Erie this year.

The population size can vary widely: the number of adult walleye surged to 98.6 million in 2005 from a mere 19 million in 1981, before dropping again. Environmental conditions are the key determinant, but it's not pollution that governs walleye numbers; severe winters are better for the fish. “Being a fat and sassy adult female walleye headed into a cold winter is a good thing,” Kayle says. “The cooler temperature helps them shut down, and allows them to avoid spending fat reserves in the winter, to put those resources into egg production.”

Spring weather stability is a second factor. “If we don’t have a lot of spring storms after the eggs are laid, that’s a good thing,” Kayle explains. “But a little bit of precipitation is a good thing. Some turbidity for a larval fish is better than none, and helps to keep them from being preyed upon.” As the Cleveland shoreline has been cleaned up, biodiveristy has skyrocketed here, but for the walleye, clean habitat isn't the only factor. Weather matters too.

The lake may be far healthier than it was in the '60s, but it still has issues.

Lake Erie’s toxic algal blooms drew national attention to Toledo last summer when a half-million people suddenly lost their drinking water. Fertilizer running off of farmland into the huge Maumee River and Sandusky River watersheds pumps phosphorous into the lake, fueling explosive algae growth. Unlike many of the pollution problems in the industrial Midwest, this one seems to be getting worse.

The loss of nearshore aquatic habitat has also been staggering. “We’ve gotten away from the natural state of the lake, and now have these engineered conditions –the shallow areas are being dredged out, and the shoreline is hardened with riprap, concrete or sheet pile,” Kayle explains. “You lose the shallow water habitat, you lose the vegetation. This takes away a lot of the ecological function of that area. We’ve lost habitat for fish to spawn, for juvenile success.”

In other words, fish are losing the habitat they need to reproduce; the habitat they need to survive past the fragile, early stages of life. It's true: in the summer, looking back toward land from a boat, all you can see is hardened shoreline spanning to the horizon for miles. We're stilled walled off from the water, the waterfront is still dominated by heavy industry and sewage treatment. We've walled the lakeshore off from its wildlife too, but diversity still bursts forth here.

At full dark, the stars overhead look like the glowing indifferent eyes of 23 million schooling walleye. Behind us, someone is operating a pile driver on the roadway, huge steel teeth smashing shut again and again. Construction projects stretch into the evening in the north, work crews racing to beat the snow. We reel in our vibrating lures with deliberate slowness to allow the fish to connect with the bait in the dark. It’s maddening to reel this slowly. The pile driver hammers to a crescendo, this is the soundtrack I would hear if I was losing my mind.

I'm numbed by vibration, blinded by darkness. I can’t see or feel much, which is why the bite is so creepy. It comes out of nowhere. The rod jerks and I drop my flask of rum, which clangs abruptly between the rocks. It’s eight feet to the bottom down there in the crevasses of the break wall. A slip would break my skull.

Men at the far end of the jetty fishing shoulder-to-shoulder, with giant 12-foot-long nets between them, rear up at the commotion. They look like medieval infantry, waiting for the charge with their lances.

There is weight thrashing on the end of my line. My brother runs down to the water’s edge to net it and notices there are two lines coming out of the fish. Someone is tangled, and someone has an 8-lb walleye.

The fish wallows in the breach against the rocks before it is scooped up into the shining light of the headlamps. The man next to us has hooked a giant walleye, full of teeth and spines. And in the fight, I have hooked his line. We are lucky to have gotten this fish in to shore.

A disproportionate percentage of walleye anglers are immigrants. There is something in the natural abundance of the United States that resonates with the newly arrived. Though we hail from every corner of the globe, we all share the uniform of the night fishing brotherhood: headlamps, flasks, long-handled nets. We are people whose idea of a good time (or worse, our very identities) is tied to windswept rock piles, crept over in the dark. We use the lake; increasingly Cleveland is learning not to take Erie for granted.

The Lake Erie walleye population might predate the lake itself – evolved from a riverine ancestor that existed in ancient waterways, even older than the glaciers that formed the Great Lakes. There are few places in the industrialized world where a species is so meaningfully connected to its unmade environment, where a species can bring so many people of diverse backgrounds together.

Fish swim up to our doorstep. Food springs out of the water. Somewhere between 20 million and 100 million adult walleye will be swimming in Lake Erie in the coming years, all naturally reproducing, springing forth out of the landscape. Despite the challenges that face this region, the Lake Erie walleye population remains healthy. For local anglers, these fish create a connection to place, and provide incentive to protect the incredible biodiversity in our own backyards.

Matt Stansberry is a Cleveland-based nature writer with three kids and a day job. He used to fly fish. Follow him on Twitter @LakeErieFlyFish.

David Wilson is a former Kent State University Zamboni driver. He currently works in graphic design and illustration at Downpour Creative. David has done illustrations for The Atlantic, Boston Globe, Men’s Journal, Outside Magazine and many other publications. More of David Wilson’s artwork can be found here.